Download

2ndfactor.c

The problem

Passwords are often seen as a weak link in the security of today’s I.T. infrastructures. And justifiably so:

- re-usability, which we’re all guilty of, guarantees that credentials compromised on a system can be leveraged on many others. And given the world we live in, password re-use is inevitable, we just have too many accounts in too many places.

- plain text protocols are still used to transmit credentials, and the result is that they are exposed to network sniffing. This is worsened by the increase in wireless usage which broadcasts information. Telnet, FTP, HTTP come to mind but they aren’t the only ones.

- lack of encryption on storage is a flaw that too often makes it way into architecture design. How many databases have we heard about getting hacked & dumped? How many have we not heard about?

- password simplicity & patterns are also factors weakening us against bruteforce attacks.

So far, the main counter measure we’ve see out there is complexity enforcement. Sometimes IP restriction, or triggering warnings on geographic inconsistencies (Gmail, Facebook). But these barely help alleviate problem.

A solution

One hot solution that is making its way into critical systems (banks, sensitive servers) is Multi-factor authentication, and by “multi” we’ll stick to 2-factor authentication (2FA) because, well 3 factor authentication might be getting a little cumbersome :). The goal is to have more than one mean of establishing identity. And as much as possible, the means have to be distinct in order to reduce the chances of having both mechanisms compromised.

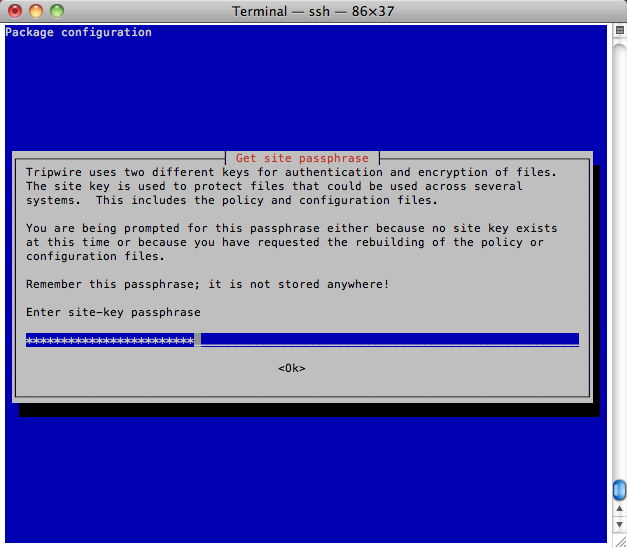

Let’s see how to implement 2FA on an Ubuntu server for SSH. Ubuntu uses PAM (Pluggable Authentication Modules) for SSH authentication among other things. PAM’s name speaks for itself, it’s comprised of many modules that can be added or removed as necessary. And it is pretty easy to write your own module and add it to SSH authentication. After PAM is done with the regular password authentication it already does for SSH, we’ll get it to send an email/SMS with a randomly generated code valid only for this authentication. The user will need access to email/cell phone on top of valid credentials to get in.

Implementation

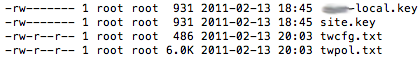

Let’s do an ls on /lib/security, this is where the pam modules reside in Ubuntu.

Let’s go ahead and create our custom module. First, be very careful, we’re messing with authentication and you risk locking yourself out. A good idea is to keep a couple of sessions open just in case. Go ahead and download the source for our new module.

Take a look at the code, you’ll see that PAM expect things to be laid out in a certain way. That’s fine, all we care about is where to write our custom code. In our case it starts at line 35. As you can see, the module takes 2 parameters, a URL and the size of the code to generate. The URL will be called and passed a code & username. It is this web service that will be in charge of dispatching the code to the user. This step could be done in the module itself but here we have in mind a centrally managed service in charge of dispatching codes to multiple users.

Deploying the code is done as follows:

gcc -fPIC -lcurl -c 2ndfactor.c

ld -lcurl -x --shared -o /lib/security/2ndfactor.so 2ndfactor.o

If you got errors, you probably need to first:

apt-get update

apt-get install build-essential libpam0g-dev libcurl4-openssl-dev

Do an ls on /lib/security again and you should see our new module, yay!

Now let’s edit /etc/pam.d/sshd, this is the file that describes which PAM modules take care of ssh authentication, account & session handling. But we only care about authentication here. The top of the file looks like:

# PAM configuration for the Secure Shell service

# Read environment variables from /etc/environment and

# /etc/security/pam_env.conf.

auth required pam_env.so # [1]

# In Debian 4.0 (etch), locale-related environment variables were moved to

# /etc/default/locale, so read that as well.

auth required pam_env.so envfile=/etc/default/locale

# Standard Un*x authentication.

@include common-auth

The common-auth is probably what takes care of the regular password prompt so we’ll add our module call after this line as such:

auth required 2ndfactor.so base_url=http://my.server.com/send_code.php code_size=5

The line is pretty self descriptive: this is an authentication module that is required (not optional), here’s its name and the parameters to give it.

send_code.php can be as simple as:

<?php mail( "{$_GET['username']}@mail_server.com", "{$_GET['code']}" ) ; ?>

Or a complex as you can make it for a managed, multi-user, multi-server environment.

Lastly, edit /etc/ssd/sshd_config and change ChallengeResponseAuthentication to yes. Do a quick

/etc/init.d/ssh restart

for the change to take effect.

That’s it! try and ssh in, the code will be dispatched and you will be prompted for it after the usual password. This was tested on Ubuntu 10.04 32b / Ubuntu 10.04.2 64b / Ubuntu 11.04 64b / Ubuntu 12.04 64b.

A few disadvantages of this 2FA implementation worth mentioning

- more steps required to get in

- doesn’t support non TTY based applications

- relying on external services (web service, message delivery), thus adding points of failure. Implementing a fail-safe is to be considered.

- SSH handles key authentication on its own, meaning a successful key auth does not go through PAM and thus does not get a chance to do the 2nd factor. You might want to disable key authentication in sshd’s config.